When my family fled Vietnam over 50 years ago, we could not bring many belongings with us. However, we did bring many memories of foods we loved and wanted to recreate in our new country. One of those foods was pâté chaud, savory puff pastry hand pies filled with a country-style pâté or meatloaflike mixture. The literal meaning of pâté chaud is "hot pastry pie", a puff pastry snack that has a long history in Vietnam and with my family.

In Vietnamese, we call these treats bánh patê sô - not too far off from the French pâté chaud. Involving culinary skill plus butter and wheat flour, bánh patê sô were considered a luxe breakfast item in Vietnam, to be enjoyed hot to showcase their crispy pastry shell. The first bite generates a flurry of pastry bits, so they're kind of messy, a bit greasy good, and very indulgent seeming.

A Saigon Favorite

When my family lived in Saigon, we often went out for pâté chaud at fancy French-style bakeries, like Givral, which made all-butter puff pastry. Lesser versions relied upon margarine, my mom recalls. Founded by Frenchman Alain Portier, Givral bakery opened in 1950 near the opera house, across the way from the Continental Hotel made famous in the Graham Greene novel, The Quiet American. In the historic postcard below, the hotel is on the right and the bakery was in the round corner building on the left. However, bánh patê sô had been in Saigon since around 1930, prepared by clever cooks and entrepreneurs such as Mrs. Pham Thi Truoc, who had a shop specializing in the pastries.

By the time my mother migrated to Saigon from northern Vietnam in 1954, a result of the Geneva Accords that split the country into two, Givral was the place to purchase French pastries and baked goods like patê chaud, cream puffs, eclairs and yule logs. Vietnamese people who opted to go southward felt that North Vietnam was conservative and limiting. South Vietnam was freewheeling, liberal and full of new ideas and foods.

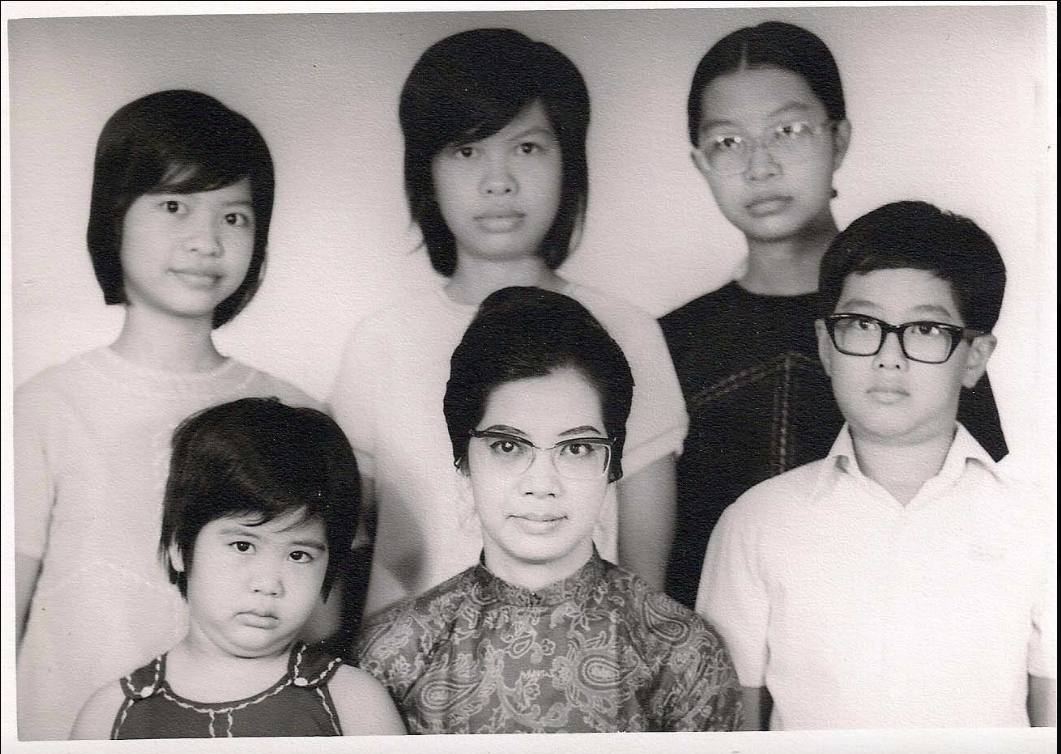

Pâté chaud is mostly a Saigon specialty. I've never spotted it in the northern city of Hanoi or central city of Hue when I visited there. In the early 1960s, Mom, her girlfriends and even my cousin, Bich Tu (who was a teenager then), were rolling out puff pastry dough at home. Butter was expensive and you had to source good wheat flour with enough gluten, my mom said.

Puff pastry needs a relatively cold environment for the dough to behave and develop the hundreds of layers of laminated dough. I have no idea how cooks in tropical Saigon, where the weather is either hot or hotter with humidity, could patiently make pate feuilletée (puff pastry in French). But they were able to do so because they were curious, determined cooks.

Pate Chaud abroad

Our family arrived at Camp Pendelton Marine Base in Southern California in May 1975 and the temperature was likely in the low 70s. Mom said that the dry, moderate climate was dreamy; she missed her father and sisters but didn't miss the weather. She had her small notebook of recipes, one of her prized possessions that came with us when we left Vietnam. But it didn't contain a recipe for bánh patê sô.

Soon after we settled into our new home in San Clemente, my mom began cranking out puff pastry from scratch to bake up dome-shaped bánh pa tê sô. She knew the recipe by heart and relied upon Julia Child's Mastering the Art of French Cooking for technical guidance. Butter was easier to buy in America and mom could pick and choose her flour (she uses unbleached all purpose).

As a result, as an elementary school kid, I ate pa tê sô for breakfast, reheated in a toaster oven until the exterior was crisp and the interior was blazing hot! There was cognac in Mom'sbeef and pork filling so the first bite often gave me a whiff of alcohol. I'd polish off the pate chaud and then go off to school, oblivious to how different that breakfast was to what my peers had eaten. I also didn't realize how unusual it was for a home cook like my mom to practice making puff pastry over and over again. While some refugee cooks tackled Franco-Viet dishes like beef stew in red wine (bò sốt vang), my mom was fixated on puff pastry and pâté chaud.

But that's what Vietnamese people are like - obsessively working to polish a skill, to mimic and master a foreign notion, and to make it their own. It's how we've survived thousands of years of foreign incursion. Strangely, even though the French colonials introduced pâté chaud to Vietnam, the pastries are not a part of the modern French repertoire. More on the interesting history of pâté chaud in this dispatch of my newsletter, Pass the Fish Sauce.

You can find pâté chaud at hardcore bakeries in Little Saigon communities and in Saigon/Ho Chi Minh City and a handful of spots. Or you can bake them yourself. I have recipes in my cookbooks, Into the Vietnamese Kitchen and Vietnamese Food Any Day. I'm also working on a new recipe for my newsletter subscribers.

Leave a Reply